No-one knows for sure how our ability to ‘reason’ developed, but it was probably not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data. Most likely, ‘reason’ developed to help us resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups. After all, our key advantage over other species was and still is our ability to cooperate in simple and more complex alliances.

Habits of mind that may seem weird from an intellectual point of view can prove shrewd when seen from a social “interactionist” perspective. Take “confirmation bias,” the tendency people have to embrace information that supports their beliefs and reject contradictory information. It is a topic that is particularly relevant in view of increasingly divided political opinion within E.U. countries and the U.S.A.

| Let’s see what researchers can tell us about confirmation bias. At Stanford University a few years back, they rounded up a group of students with opposing opinions about capital punishment. Half were in favour and thought that it deterred crime; the other half against it. All participants were given two specially written studies, one with data in support of the deterrence argument, the other calling it into question. Both were designed to present objective and equally compelling statistics, but what happened was that students who supported capital punishment rated the pro-deterrence data highly credible and found the anti-deterrence data unconvincing. |

Why do we do that? One theory is that for our ancestors, hunter gatherers, being able to reason clearly and precisely was of no particular advantage, yet much was to be gained from actually winning arguments, however we went about it. Back then, life was of course much simpler and they certainly did not have to contend with fake news or Twitter feeds.

| It’s worth also remembering that people also believe that they know way more than they actually do. Ask how a toilet works and most will say that they know. Ask them however to provide written step-by-step explanations describing how the toilet works and… most people fail. A zipper anyone? Such everyday objects are often more complex than we realise but the thing is: we’ve been relying on each other’s expertise ever since we figured out how to hunt together. In our day-to-day life, we can collaborate so well, that we don’t even think about where our own understanding ends and others’ begins. |

| A survey conducted in 2014, not long after Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, asked respondents to define how they thought the U.S. should react, and subsequently, whether they could identify Ukraine on a map. Interestingly, the farther off base they were about the geography, the more likely they were to favour military intervention (the median guess was wrong by 2,500 kilometres). This is just one of many studies that show how having strong feelings about issues does not necessarily come from having a deep and thorough understanding of those issues involved. |

How about something more prosiac such as performance-based pay for teachers? Researchers at Yale asked participants to rate their positions depending on how strongly they agreed or disagreed with such a proposal. But when instructed to explain the impacts of implementation in as much detail as they could, most people ran into trouble. Here things got interesting; asked again to rate their views, they ratcheted down their intensity, either agreeing or disagreeing less vehemently. And here perhaps is a little candle for our dark world.

| If we - or CNN or the BBC for example – would spend less time pontificating and more time working through the implications of policy proposals, we might all realize how clueless we are and moderate our views. But first a word of caution: such an approach won’t be easy. You see, research suggests that we experience genuine pleasure - a rush of dopamine - when processing information that supports our beliefs. So the problem is, it actually feels good to ‘stick to our guns’, even when we are wrong! Dale Carnegie, author of the perennial bestseller, 'How to win friends and influence people', told us back in his original 1936 edition that providing people with accurate information won’t change their minds; they simply discount it unless you also appeal to their emotions. |

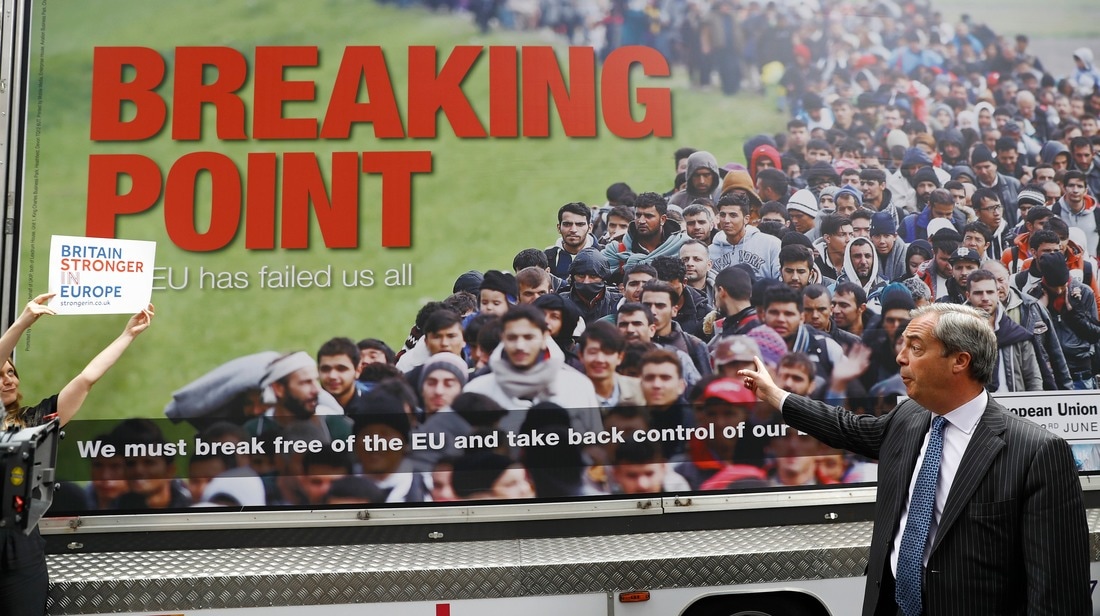

| When Farage used a poster featuring asylum seekers on the gates of Europe to symbolise the supposed ‘threat’ of economic migrants coming from Eastern European countries to the UK, he insisted that the poster was an "accurate, un-doctored picture showing the strains facing Europe”. And that is indeed part of the truth. Because of the controversy, news channels and newspaper journalists gave much more exposure to the provocative poster than it might otherwise have received. |

| As a footnote on ‘How best to influence others’ – perhaps we should look to inspiration from ancient Greece when moving from simple facts to ‘emotional’ influencing factors. When building an argument, they would famously employ a combination of Ethos, Logos and Pathos Ethos (Ethical appeal): means first establishing your credibility – showing that you know what you’re talking about; such as presenting both sides of an argument accurately. (Ethos is the Greek word for “character”. The word “ethic” is derived from ethos.) |

(The word “logic” is derived from logos.)

Pathos (Emotional appeal): Don't forget to use words/visuals that create a strong emotional response. Storytelling for example or connecting on a personal level – expressing similar desires/interests etc.

(... Pathos being the Greek word for both “suffering” and “experience” and giving us both the words “empathy” as well as “pathetic”.)

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds

RSS Feed

RSS Feed